Live surgery has become a popular format used in many educational surgical congresses/meetings. Live teaching of anatomy and surgery has been relevant since the 18th century to train generations of surgeons through observation. The first laparoscopic operation broadcast over the internet took place in 1996. However, concerns have gradually emerged about patient safety and consent, ethical issues and the real educational value of these live broadcasts.

A spy in the operating theatre

For some surgeons, being observed while operating can create stress, while for others it is a routine.

A systematic review carried out in 2022 (Carbonara et al., Eur Urol Focus)1 showed that the majority of procedures retransmitted in Live Surgery concerned urological surgery, without showing any increase in the risk of surgical complications in this specialty unlike other surgeries (ophthalmology, ENT, general surgery…) or other interventional procedures (cardiology, digestive endoscopy…)1.

Surgical results and patient safety

For urological surgery (in particular robot-assisted partial nephrectomy), post-operative results were not altered by live surgery compared with non-live surgery, in terms of blood loss, warm ischaemia time, surgical margins or length of hospitalisation2. Regarding robot-assisted radical prostatectomy, however, some authors noted an increase in median operative time3, or surgical margins (linked to the desire to present maximum nerve preservation for educational purposes), but with no increased risk of recurrence. There was no risk concerning endo-urological surgery or interventional cardiology1, but an excess risk of surgical complication was noted in the field of bariatric surgery4.

Educational value of live surgery

In the review by Carbonara et al., the educational value of live broadcasts of surgical procedures was reported1. Questionnaires carried out again in the field of urology showed that viewing live commented surgery seemed essential to respondents in terms of surgical training, but the majority of studies present biases and the absence of objective evaluation1.

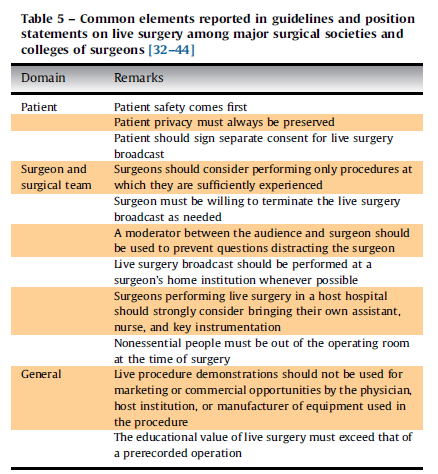

Scientific societies and recommendations

A number of scientific societies have issued recommendations concerning the performance of live surgery, in particular the European Association of Urology. These aim to maximise patient safety (by signing a specific consent form for live surgery) and minimise surgical risks (by avoiding distracting the surgeon with untimely questions during live surgery, and by using a single moderator as the surgeon’s main contact). Other surgical scientific societies have taken a stance against performing live surgery at congresses (American College of Surgeons and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)1. The Japanese surgical societies have proposed, for example, that live surgeries should be performed exclusively at the operating surgeon’s institution (discouraging surgeons from travelling to operate internationally, away from their hospital, with the operator also affected by potential jet lag), without performing complex operations, and favouring standardised5 procedures.

All the elements common to the various learned societies are summarised in Table 5 of the review by Carbonara et al., and emphasise patient safety above all. An alternative to live-surgery could also be the dissemination via platforms or webinars of pre-recorded videos with commentary6.

References

- Carbonara et al. Eur Urol Focus 2022, PMID : 34148861

- Mullins et al. Urology 2012

- Ogaya-Pinies G, Eur Urol Focus 2019

- Ruiz AG, Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017

- Japanese Society of Cardiovascular Surgery. Guidelines for live presentations of cardiovascular surgery.

- Smith A, BJU Int 2012

Article written by Charles Dariane.

Read more

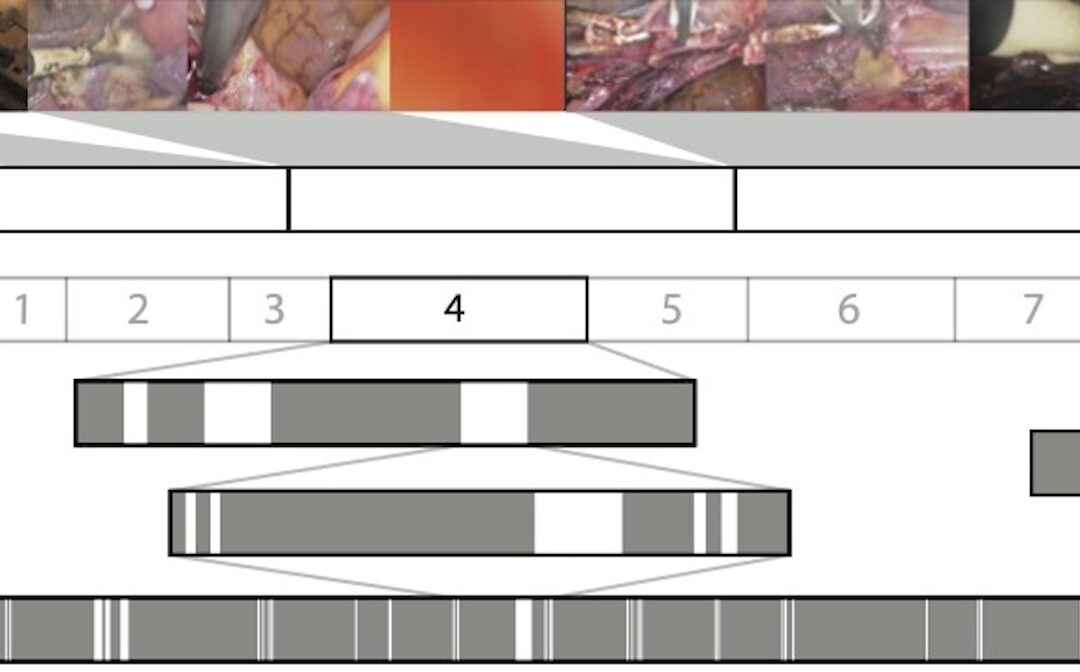

Surgical Video Summarization: Multifarious Uses, Summarization Process and Ad-Hoc Coordination

While surgical videos are valuable support material for activities around surgery, their summarization demands great amounts of time from surgeons, limiting the production of videos. Through fieldwork, we show current practices around surgical videos. First, we...

ResoMeds: a social network sharing videos

Case reports enrich medical knowledge and training, and improve practice [1-4]. However, their publication is often limited in existing journals [5]. We aim to highlight the importance of creating a platform for physician exchange to promote peer learning, case...

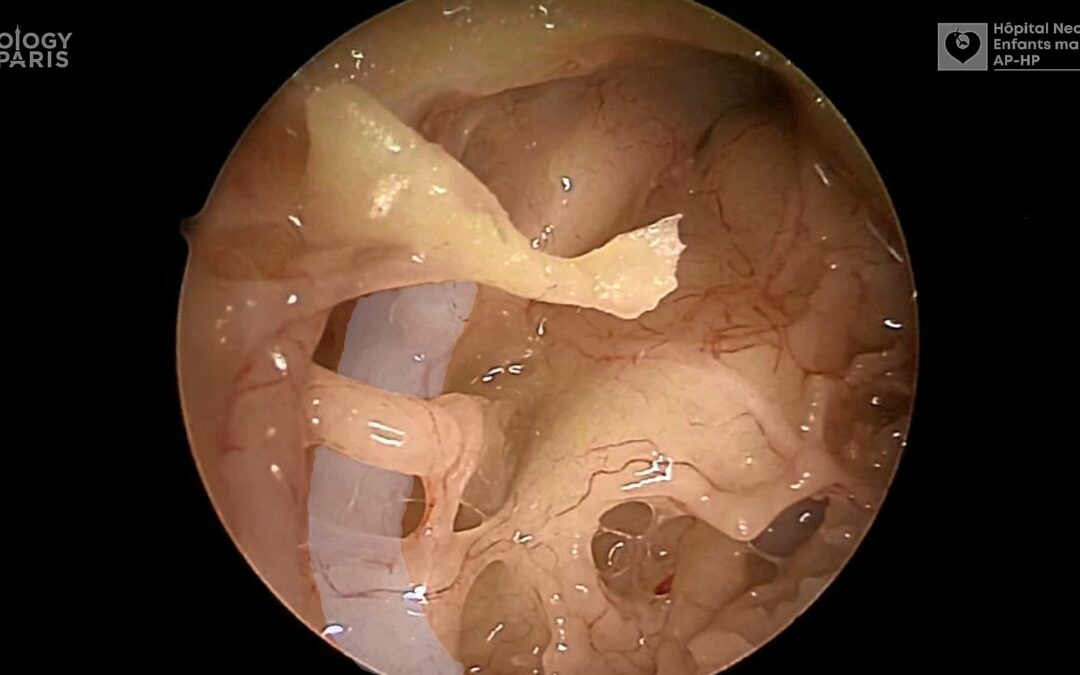

Videos improve knowledge retention of surgical anatomy

In otolaryngology, a new publication shows that an educational video improves anatomy learning and knowledge retention in the long term. This study conducted by the ENT team at Necker-Enfants Malades, APHP (Université Paris Cité) and led by Pr François Simon shows the...

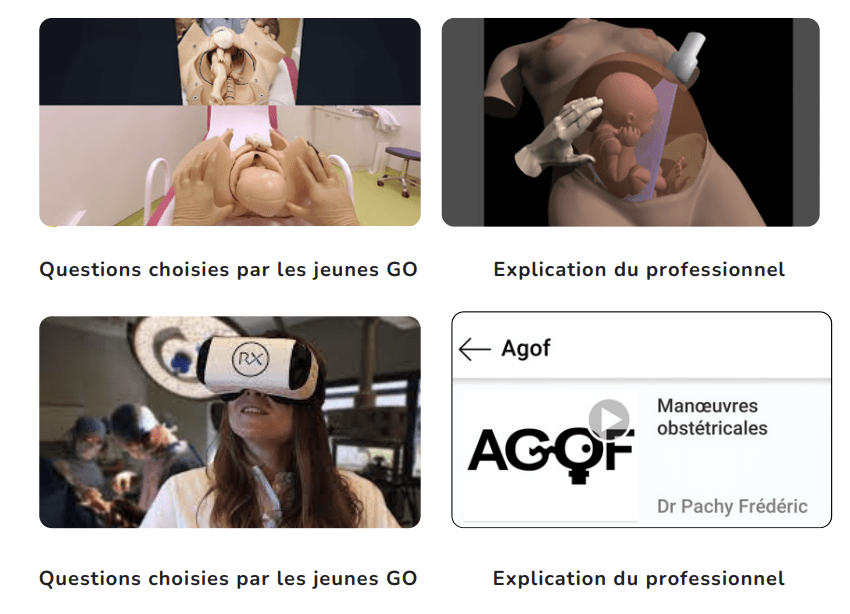

Surgical videos: using the most efficient medium. AGOF’s associative experience

In 2010, the French National Authority for Health (HAS) issued the famous slogan for apprentice surgeons: "Never perform surgery on a patient for the first time" (1). It is sometimes difficult for a young surgeon to accept that he or she has not received sufficient...